Your Body on Video Games: Ramin Shokrizade on the Neuroscience of Games

Noted video game neuroeconomist Ramin Shokrizade came to games from athletics.

Ramin observed that many of the physiological mechanisms for eliciting peak performance in athletics had parallels in the behavioral patterns which make or break a video game’s success. That has led to Ramin’s career in the video game industry as a designer of the “metagame” aspects of a game.

We sat down to hear about this burgeoning area of the job market and how science-informed game design has parallels to many areas of software engineering.

Full text transcript below the fold

Audio:

Play in new window || Download

Show Notes:

Text Transcript

Max: Welcome all, Max of The Accidental Engineer here. Today, I have the pleasure of having Ramin Shokrizade join us.

Welcome, Ramin!

Ramin: Thank you, Max.

Max: Ramin is a well-known game economist with an extremely interesting background. I don’t know where else to start but I guess let Ramin tell you a little bit about himself, himself.

Ramin, do you mind mentioning to people the long version of how you got into video games?

Ramin: Sure. I didn’t go into my current career path thinking I was going to end up where I was. It just kind of accidentally happened :) in the beginning, I had a … I encountered my experiences of addiction and such at a very young age. At the age of five, I started smoking which was acceptable in my household. After six months, I worked my way all the way up to the unfiltered Camels. Then my body just said, “No, this isn’t going to work for us.” I developed severe asthma.

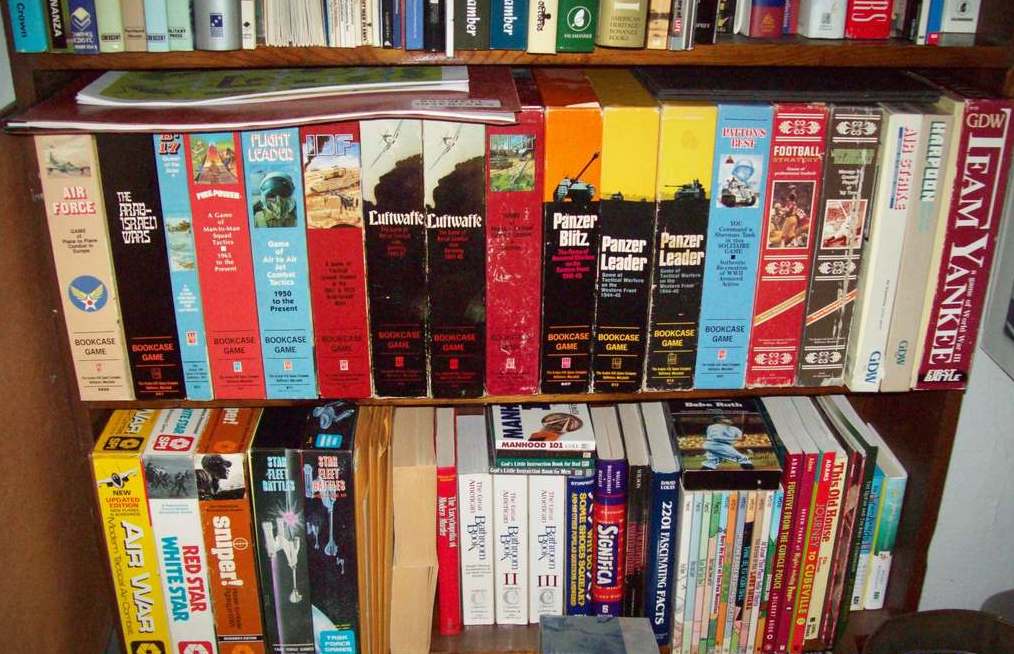

I wasn’t able to do physical activity–I wasn’t allowed to do PE in school for the next nine years. Instead, I got very much into gaming. Back then it was what you would call I guess “analog gaming,” like board games and Avalon Hill games and chess, things like that.

But at the same time I grew up in Venice Beach where the Muscle Pit was a big deal and I used to go there all the time and hang out with old masters that were body building and doing all kinds of aerial gymnastics right before it became a thing.

They convinced me that anything that was ailing me I could overcome if I was just determined enough too work through it. So at the age of 14, I went out to the track, brought my asthma pills with me and just started running until the asthma attack started.

I took my pill, laid down the grass, had the attack and survived it. It was painful.

The next day, I came back and I did it again and the next day and the next day and the next week and the next month and after three months of doing this everyday, I couldn’t trigger an asthma attach no matter what I did. I threw my asthma pills away.

Ultimately, instead of going into the type of quantitative fields that you would expect somebody with a real strong math background to go into, I ended up becoming an exercise physiologist.

My estranged family ended up leaving me homeless at the age of 17 but by then I was already so well-known by the local track community because I went from zero to super fanatic about fitness during this period. They took me in and I ended up being coached by world record holders Tommie Smith. Before I was even an adult, I was what, 17 years old training under him.

Max: So you found your path to an undergraduate degree at UCLA, is that right?

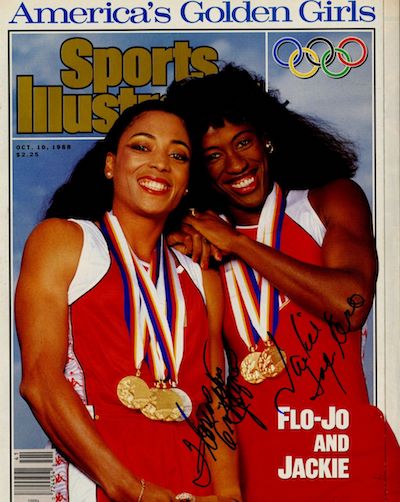

Ramin: Yes, I ended up graduating at UCLA and while I was there, I was on the coaching staff. I was training the UCLA women’s track team and the USA Olympic women’s track squad was training with us there at Drake Stadium. I ended up becoming the trainer for both the UCLA team and the USA team and the USA team went on to set … My athletes went on to set several world records that are still standing today and are considered unbeatable.

Max: This includes Jackie Joyner-Kersee and Flo Jo?

Ramin: Exactly. Exactly. You’ve done your homework.

Max: Of course. I mean, your story is really interesting. I think our audience would be very interested to hear how the experience you got in rehabilitating your own body from having asthma and heavy smoking to being a track athlete ties into your current career in video game economics and designing video games.

For our audience that doesn’t know, what is it that you do as a video game economist?

Ramin: Well, that’s just one of the hats I wear. But I would say more recently I call myself a game “neuroeconomist” because I’ve added the neuroscience in it so much.

Basically what I do is I create the meta games for large games as a service. If you play a game where you’re likely to be playing with other people and it’s free to play but they want you to spend more, then the best way for them to do that is to create these “meta game” systems where there’s progression systems and competition and you’ll want to get ahead and you want to feel good.

All that stuff that makes you feel good between the gameplay sessions because you’ve achieved something or advanced in some way, that’s what I design, in addition to all the business models.

All the numbers that support that connect all the game moments together into a game as a service product–that’s what I make.

Max: You’re actually our first guest on the show as a video game industry member. You mentioned “free to play.”

What’s the distinction between a free to play game and otherwise?

Ramin: In the past, most things that you’re used to buying are retail products. You pay for it and now you get it and you own it.

In free to play, we just give you the game upfront and you can play and you don’t have to pay us at all. But the trick is how do you get someone to pay for something that you’ve already given it to them for free? That’s actually a very complex mathematical and scientific question. Increasingly, the solution is to use mechanics that are known to trigger either a compulsive or an addictive response to force the player to spend money on your product.

Max: Makes sense. I guess one way to describe that distinction between free to play and pay to play is that with free to play games—as a creator of free to play games–there’s adverse selection, where your audience of people who play free-to-play games are people who are less likely to spend money than someone who’s paid to play a game? Is that an accurate representation?

Ramin: I’d say that while that’s possible, I think the most important distinction is that because it’s free to play, the barrier to entry for the consumer is set to almost zero other than just the effort it takes to download your game. Because of that barrier to entry is low–they’re very likely to install your program whereas otherwise they might not, if there was any doubt about your product.

So that gets your products under the nose of the consumer where hopefully the rest of your mechanics will lure them into spending.

Max: One of the interesting topics I’ve seen you write about as a contributing author on Gamasutra and you’ve spoken about as a guest on NPR is about the hormonal feedback loops that exist when people play games.

Tying it back to your experience doing athletics and coaching, what’s the tie-in between humans’ hormonal responses to video games and humans’ hormonal responses to exercise?

Ramin: When you’re talking about training for an athletic event–besides that you’re talking about actually growing a human being–there’s very specific chemicals released and certain patterns and rhythms that can be optimized for maximum growth. Here, I’m talking natural, not by giving a drug. This requires a person to switch between exercise and growth phases.

These are two sides of the autonomic nervous system, the sympathetic and the parasympathetic nervous system. Normally, in a healthy individual, you cycle naturally between these two sides of the autonomic nervous system throughout the day, usually first thing in the morning, you spike with a surge of cortisol and your sympathetic nervous system becomes active. You go around. You’re alert. You’re focusing. You’re doing all kinds of stuff. Your appetite is diminished.

Then as the day goes on, you get tired, you relax. Your appetite starts to build. You’re relaxed to eat. You go to sleep. While you’re sleeping, everything you just ate is converted into tissues, to repair any damage that might have occurred during the day when you’re exercising.

When you’re exercising on an athletic level, you’re intentionally trying to stress the body to trigger greater growth response during your downtime, during your parasympathetic nervous system activation.

Max: Then when it comes to games, what is the general pattern that a free to play game has on a player’s nervous system?

I guess that it doesn’t exactly parallel the hormonal response to performing exercise, in that people aren’t playing games to strengthen their ability to play free to play games more but there is a hormonal aspect which you’ve written about at length that I’m curious if you can tell our audience about that keeps people coming back to free to play games?

Ramin: Right. There’s a balance between the two sides of the nervous system. But increasingly in our society, we’re pushed to do more and be more and more productive.

So there’s a lot of emphasis on us being alert all the time, it’s almost like sleep has become a dirty word. We’re obsessed with coffee. We’re obsessed with stimulants. People will brag about how much coke or meth they do or whatever and how long they can stay awake. Gamers often like to brag about how long they could go on a play session without sleeping. When you do this, you’re stressing the body quite a bit. Without the equivalent rest stage, you’re doing damage over time, not only physically but also mentally.

At the same time, in the gaming industry, we found out that the gaming industry is learning the science very slowly. So at this point, they’ve learned the circa 1931 neuroscience. We’re almost 100 years behind as far as science but back in 1931, a guy named Dr. Skinner developed an experiment that showed that we could trigger the release of dopamine in the human body by using these randomized reward schedules. This would soon become addictive. You could train an animal to do basically whatever you wanted by linking this randomized reward system to the behavior you want to induce.

Max: So the low tech version of a Skinner box might be a casino slots machine, I guess?

Ramin: Yeah, I would say that that was correct.

Max: I guess there’s plenty of instances that we might be able to give as examples of this type of a Skinner box mechanic existing in video games today.

But what are some of the hormonal downsides to playing the Skinner box game for long periods of time?

Ramin: Dopamine is on the upside of the nervous system, the sympathetic side, the part that keeps you alert. It keeps you stimulated. So if you get in a stimulation loop, like the people who get in front of a slot machine in a casino and they basically just go until they run out of money, when you stim a person like this, you can create a situation, what I call “stim lock” which is that exact situation where somebody stays in front of the machine until they run out of money or someone interrupts them and they’ll lose track of time and being stimulated that much creates a tremendous amount of stress in the body.

Without anything else to counter that, the person will be sleeping much less. They’ll be prone to depression, especially when they stop playing. They’ll have more illness. They’ll just overall have a decrease in health because they’re not recovering.

Max: One of the topics you’ve written about is sustainable games, ones where players won’t get so burnt out that they leave forever and that there are mechanisms that can be put in place designing the game differently so as not to overstimulate in this way.

What are some of the game mechanics like that that prevent the overstimulation and people abandoning the game?

Ramin: Right. Well, when you try to just go for the quick stim, your consumers, your players will become fatigued. Once they become fatigued enough, they will stop playing or their family or their work will make them stop playing because it’s interfering with their other real life activities. So you’re lucky if you get even a month out of the consumer.

Even if you think you’re doing great on the first few days, they drop off so rapidly that you don’t end up making much money. Whereas if you can get a game that actually feels right to the consumer because you’re hitting it on the chemical level, even though the consumer isn’t aware of what’s going on inside them chemically, if they just feel like their stimulation needs are being met but they’re not becoming fatigued over time then they can keep using your product and form a bond to your product and have it become their entertainment avenue of choice which is the most ideal situation.

That’s why the games I’ve designed like World of Tanks Blitz perform so well is because people keep playing them. They don’t just play it briefly and stop. They enjoy them. They bind to the product and they just feel good enough but without becoming tired, that they just keep playing it.

Max: You described some external stimuli that stop people from playing games that have them in lock like family or running out of money. But what are some internal game mechanics that for examples the games you’ve worked on have to prevent people from burning out?

Ramin: Well, once you’re in the game and you become immersed, you can get into the stim lock and you can forget the rest of the world. The prevailing wisdom is that the longer a person plays your game, the more they will spend on your game. I don’t necessarily think that’s true. I think that’s an oversimplification. So they try to stim lock you so that you won’t leave the application and do anything else. I think that will inevitably set a conflict between your game and the rest of the life that your consumer has.

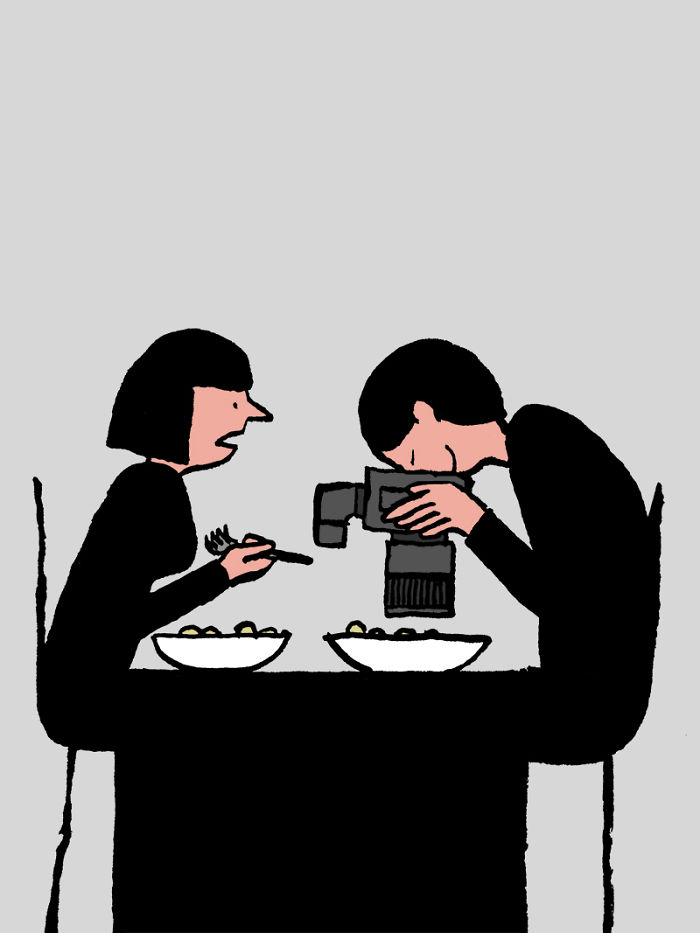

Instead, what I do is I set up emergent breaks so that between a gameplay session which could be up to 15 minutes long, there’s a break and then you engage with the meta game and do a relaxing activity that gives you time to recover before you go back in and start hitting it.

Max: To draw a parallel to some other types of software that one might not normally think of as being a game, one dominant type of software I’ve seen in our age that follows the stim lock pattern that’s not quite called a game is Facebook and Snapchat and Instagram.

Ramin: Absolutely.

Max: You haven’t written anything publicly about the topic but I’m curious if you have any guidance for our listeners about what patterns these social media apps have that mirror the types of Skinner boxes that exists in video games? Are there any?

Ramin: I mentioned the words “social media” probably for the first time in my physiology of gaming paper recently which I think you’ve read. There’s a reason why I’m a little reluctant to make the crossovers there because social media is such a big part of our lives.

When you start describing what’s going on physiologically during social media, you’re describing a huge shift in the physiology of not just millions but billions of people.

The information we’re getting shows that that’s not a positive shift. It’s actually lowering lifespans, lowering mental health and it’s become a big enough concern that even former leaders of Facebook have come out and said that we shouldn’t have this, we’ve created a monster.

Max: One of the reasons I bring it up–not to put you in a difficult position to talk about a topic you might not want to talk about–is that it seems to me like those software applications, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, are great examples of software games that have figured out how to maintain the lifetime value of a customer over a really long period of time.

Like in the way that you have perhaps an Instagram profile–it’s a lot harder to shutdown an Instagram profile hormonally than it is to maybe cancel a game membership or just stop playing a game.

What is it about social media software that makes it hormonally hard to stop playing? In contrast to maybe what people would more conventionally think of as video games?

Ramin: Right. Well, the part of social media programs these days that the developers are attempting to optimize is the dopamine delivery and that’s how they will intentionally space out notifications but make sure you keep getting hit with notifications in almost randomized fashion throughout the day to keep you engaged, because again, the longer you’re engaged, the more likely you are to spend or at least they’re just depending on advertising dollars they want your eyes on their product as much of the day as possible to the point that they will even send you notifications when you’re sleeping to try to pull you out of your sleep and back into the application. That’s the dopamine level.

They know that by randomizing this and that’s why sometimes when somebody sends you a message, you don’t get it right away, is because their intentionally trying to optimize the delivery times to maximize the hits you’re getting so that you’ll be maximally stimulated by the product. That’s the part that they understand or are increasingly understanding. The part that they don’t understand which probably the more potent aspect of their products is how this interacts with the hormone called oxytocin which is oxytocin essentially is a hormone that when you engage in social activity with another person or even with an animal, if you consider that person to be part of your tribe then it lowers your anxiety. It increases your trust for that person. You get a generalized sense of wellbeing.

If it’s a romantic kind of connection, the amount of oxytocin release can be so much that you can literally be on a very intense high and be very spacey. By using this, they can pull you in. I personally think that oxytocin is the most powerful drug we know. You can be under a strong oxytocin high, you can be made to do almost anything. But this is an important survival characteristic for humans because when we feel a strong enough attachment to someone else and that other person’s threatened, we will literally put our bodies between the person we love and the tiger or whatever is threatening them and sacrifice ourselves. That’s an incredible powerful survival mechanism because it brings humans together and allows them to overcome things like tigers that individually they would have no change of defeating but as a group they could.

Max: In social media settings, you have your tribe present. You feel you’re getting constantly reminded through the application that members of your tribe are seeing your activities or you are able to communicate with members of your tribe where you might be able to communicate as efficiently with people or bond as efficiently with people and produce oxytocin as well when you’re interacting with anonymous people over the internet playing perhaps an anonymized game. One of the things that I suspect and I’m curious to hear your take on this, with social media, there’s also a serious narcissistic component to it which is the reminder notifications and I think this is where Snapchat was a big innovator over Facebook was and I’m not sure why Facebook didn’t act on this sooner is giving you information about who is seeing your activity on the social network.

So Snapchat, one of their features was when you send a message, they’d let you know if somebody read your message. When you’d post a story publicly to all your friends or if you had a public account, you could see exactly the usernames of who had seen your posts. I’m wondering perhaps maybe was there a reason Facebook didn’t make that data more visible to their users about who is viewing your Facebook profile? I mean, was this really such a big innovation by Snapchat to give people insight to who is seeing their activities on the site?

Ramin: I would say that while they understand 80 … Or we have a pretty good understanding in tech 88-year old neuroscience when it comes to dopamine delivery and optimizing for that, most of the research on oxytocin has occurred in the last 10 years. Before that, we really had no idea what it was or what we did know was just pretty misleading. With something like a like, the data was showing that it was improving engagement but because the lack of appropriate scientists in social media, we didn’t know why. So we just thought, “Let’s boost these likes because if it works a little, let’s make it work a lot.” So it became all about the like. It became all about showing your photos. It became about getting viewed or liked or as much positive reinforcement on that level as possible.

Which is a very weak type of oxytocin stimulation but in this case, it’s just a massive amount of it. So instead of it becoming the type of quality we would have in real space like having a hug or talking to somebody looking into their eyes and seeing them smile, instead of that type of quality, instead we have this massive amount of quantity of very low quality stimulation on the oxytocin sphere. So all these likes, people are liking their pictures. The more clothes I take off on my pictures on Facebook the more likes I get so I start taking off more and more clothes and pretty soon I’m a lingerie model at the age of 13. This is how we train our children.

Because of it, this latest generation is supposedly three times as narcissistic as any previous generation. That’s because we’ve trained them to be that way. We reinforce them that this is what you have to do to be liked in our society. It’s not the way it used to be at all.

Max: One of the big distinctions I think people might draw between a social media app like Instagram, Snapchat, et cetera, and perhaps the video games that’s you’ve worked in your career is that there’s lot less user generated content in a video game. Why is that the case? Do you expect there will be more games that coming out in the near future with user generated content?

Ramin: I would say again it’s because the people who make computer games are not particularly highly educated people. They’re mostly they knew somebody and they got into the field or they know how to program but they don’t have a science background. So they’re basically just trying to recreate the movie industry into computer games but not without the understanding of what their role is actually in the economy which is they’re there to provide recreation to consumer, to meet consumer needs but they don’t know what those consumer needs are so they’re not quite hitting it right.

Max: I mean, I’m not totally I buy it. In a capitalist economy, it seems like if there was an opportunity to make user generated content based video game, it would be made.

Ramin: Okay, let me give you an example of two user generated content games that have been highly successful but by accident because the people who made them didn’t know what their … Why they would be successful. The first example I would give, it would be Pokemon Go which was developed based on a previous game where the users actually went out and located these stops, Poke stops that gets the Pokemon Go and uploaded them and each of them had like a picture and showed some historical information about the location.

These are the best part about Pokemon Go for me is I can go into a new town and use Pokemon Go to go from Poke stop to Poke stop and learn about the culture of the new town I’m in from what it says on each of the Poke stops. Each of those Poke stops is uploaded by a player that did that for free. This was done worldwide. So you’ve got a massive amount of global user generated content. That game would just not be nearly as interesting without that user generated content.

The second example I would give is the game I talked about at the game development conference in Saint Petersburg, Russia in 2016 and that game is called Tinder.

I gave a presentation. I explained why Tinder was the top mobile game in 2016. This talk was three months before Pokemon Go game out and basically told them that once we create an even more social game, that there’s a huge pile of money just sitting on a table out there and as soon as we figure out how to create social interaction on our games, even more than in Tinder, that money will just be there for the taking for whoever hits it first. Three months later Pokemon Go came out and that was that because people are playing in the streets and meeting new people that they may have lived next to for five years and never met before but all of a sudden now they’re getting out and meeting all their neighbors. It was huge.

In Tinder, you’re again meeting the community but again, it’s just a lot of high quantity but low quality interaction. The research is showing that over time, in all metrics evaluated, all metrics of mental health, they go down over time as you use Tinder. People become more and more unhappy as they use Tinder. So it’s creating the right stimulation but it’s the wrong quality and it’s actually backfiring.

Max: That’s interesting you mention it. I mean, Tinder I think is another example where you get the same type of feedback loop as Snapchat where you don’t get visibility into who’s viewing your profile but you definitely get a certain type of narcissistic validation from people swiping on your and validating that you are somebody that other people want to engage with. At the same time, I guess it doesn’t lend itself to at all building any kind of tribe.

Ramin: Well, it’s all user generated content though. So that’s great because you don’t have to lift a finger. The users are bringing all the content to you. It’s at least at first glance, it’s very high value content because you’re looking at pictures that are again designed to be as appealing as possible because these people have been through the Facebook treadmill since they were 13 or younger and have learned to model for these pictures. In theory, you can get laid on Tinder and that’s worth a lot to users. That makes their user generated content a very high value to the consumer, except for the allure isn’t really as good as the reality and I think it’s men specially their connection on rates on Tinder are 1.5%.

In many cases, when people do connect on Tinder, they’ll end up having casual sex. It doesn’t go anywhere. They come into contact but they don’t have the communication skills or the social skills because they haven’t developed those on Facebook or Tinder or anywhere else in the new age to develop that relationship. So they end up becoming just more and more anxious, depressed. They’re not getting the real oxytocin that they would get if they were reaching to the point where they’d be looking into someone else’s eyes, seeing them smile or hugging them or some sort of real social affirmation that they would tell them that they matter to someone else.

Max: Your work in video games has largely been not in these type of social games like dating apps or I guess one might even call social media apps like Instagram and Snapchat as games but you’ve worked more with conventional video games I guess is the best way to call them. Do you might telling our audience a little bit about the types of games that you work on or that you are currently working on?

Ramin: Well, I mean, much of my work was considered theoretical for years and for years I was told, “Well, no. What you do is just theoretical. So we doubt it would actually work in a real game.” So it wasn’t until I started getting hired … It took a few years before the big companies like Microsoft or War Gaming or Take-Two Interactive started hiring me. In each case, they usually kept it extremely secret that they were hiring me so people wouldn’t know that I was working with them or whatever I was doing. Then eventually I started getting the data showing that my methods were very successful. But have I translated that to social media? Once you’re type casted as a gamer, it’s hard to jump to another industry.

Soon after it was accepted that my research was effective, I ended up getting tapped by the International Regulatory body in 2013 to advise them on how they should regulate computer games worldwide. I was the only independent adviser to the ICPEN which is the International Consumer Protection and Enforcement Network when they held their first and so far last global summit on how to regulate computer games. I basically spilled the beans that I think that made a lot of people uncomfortable that didn’t want the beans spilled.

Max: The bean spilling refers to distinguishing between games that prey on people’s addiction versus the gaming industry labeling that type of consumer behavior as engagement, I guess. Is that a fair description how industry calls engagement engagement and-

Ramin: I would say that in the olden days when we thought of entertainment, it meant we’d go out to the theater, we saw a movie, we saw actors interacting and it was just a fun time.

Now, I showed how everything in games, even aimed at children as young as six years old is designed scientifically or engineered in a way to stimulate and or mislead the consumer in a way that will get them to spend money. In the case of six year olds, this is pretty easy. So when you point a whole room of Ph.Ds at a six year old, the six year old really has no chance. So I’ve showed them slides of this exact kind of behavior, this methodology. In the particular, the product I probably spent the most time focusing on was a Disney product. This didn’t make Disney too happy with me. Disney is a big player in this market.

When I came back from the summit in Panama and I was scheduled to present my findings at GDC the game developers conference, I had been double confirmed to give two talks at GDC and then both are just canceled at the last minute and there was never any explanation. I was supposed to talk again this year, same thing happened.

Max: So besides the industry being weary of spokespeople over the issue of mental health and negative effects of gameplay in the threat of regulation in the business, I think a lot of our audience are curious about the types of games that you work on and what types of game dynamics it is that you personally give input on. What games are you working on these days?

Ramin: Well, these days, I’m trying to actually build the first games that have ever been optimized specifically for oxytocin delivery. I don’t think that’s ever been done before. I mean, in a couple of cases it’s happened a little bit by accident like with Pokemon Go but no one’s ever really tried to actually make a game that boost oxytocin in the users. So really, that’s my goal with the two products I’m working on right now. One, it’s been in development for over a year. It doesn’t have an official name. It hasn’t been announced.

It’s a massively multiplayer space game similar to Eve Online but it’s with all the boring parts taken out. It’s all combat but the focus isn’t on me being the most powerful person in the universe. The focus is entirely on my team being the most powerful team in the universe and so I reward team play, not the individual and I’m kind of a stickler about that be I want to de-emphasize the narcissism push that we have on our current games and get people back to focus more again on the social interaction. So that’s-

Max: For members of our audience that aren’t familiar with Eve Online, do you mind giving people a sense of what are the defining characteristics of that game Eve?

Ramin: Eve Online is interesting in that it’s a game that launched in 2003 with just one server, and they’ve never added another server and that one server has been going continuously for 15 years. It’s one of the great industry success stories.

But they’ve never been able to move past the initial design to make the game better. They’ve had very little luck with that. The game hasn’t really exploded like it would I think if they solved some of the core problems in that product but it still just stayed steady for 15 years and people just play it year after year.

It’s also very unusual because it had a complete economy that was very similar to the real world economy and that allowed me in the first year when it was out to actually make some observations about real world economies by watching the way the economy developed in Eve Online.

Max: I would love to queue up our audience, go check out Ramin’s article on all those article is posthumously published after the housing crash 2008, Ramin had some interesting commentary to say about the dynamics he noticed in Eve Online’s gameplay and the dynamic that exist in the real estate housing market in the United States. I’ll include a link to that in the description notes. One thing I want to point out for our audience that I don’t think you mentioned is that Eve is a massively multiplayer online game of course that has a I guess a real time strategy component, is that accurate description?

Ramin: You are the ship and you go out and you blow stuff up with your ship. If your ship dies, you’re like a little pilot in your ship and you end up … Your corpse floats around in space in a little pod and if they shoot your pod that’s the end of you then you have to be reconstituted somewhere else at a penalty.

Max: So not quite real time strategy game but more like, I don’t know, is a role playing game a proper description?

Ramin: Somewhat. I would say it’s social in the sense that you … There are a lot of interdependencies in order to make … Everything is a player driven economy in that game. So everything that you’re playing with has been built by another player. Some of the bigger things require a lot of people to work together to build. I was one of the first players and I was the richest player in Eve Online when it first came out. I was building some of the first battleships in that game. I had 5,000 people a day working for me that didn’t even know they were working for me. But everything they collected in a day went to me and they got paid by me. All of those resources were put together to build the very first battleships which people were paying me a thousand real dollars for a battleship in the first couple of months when that game came out.

Max: That’s crazy. I forgot to mention and we didn’t really get to this in your intro about how for a period of time, you were legitimately making an income off of selling these in-app achievements or in-app resources that you harvest, maybe not in the way that is now the reputation for gold farming in World of Warcraft but this was a real outlet for you, I guess. Do you mind sharing with our audience about that experience? I mean, you kind of were touching about this with this battleship constructing in Eve Online. But what are the real dollar types of incomes that people can find through playing games?

Ramin: I was big into fitness and I was very successful as a coach but I got hit by a drunk driver in 1994 and while I was reassembling myself, I got into online games just as they were going online. When a game came out called Eve Online in 1999, no, I’m sorry, EverQuest in 1999, I was playing this.

I was one of the top players and people started offering me money for items that I was collecting in the game. I was like, “Wow, I’ll give you this sword and you’ll give me $100, really?” I was just so fascinated by this that I quit my day job and I just started collecting all these virtual goods and selling them as a living. It became such a … I just got this strange feeling from it that I thought people should know that this is a thing and I went to the Los Angeles Times.

To my surprise, they responded to me. They hooked me up with the tech editor, Ashley Dunn, and we co-wrote the first paper on virtual goods sales in April of 2000. I was so fascinated by what caused people to want to spend money on things that didn’t really exist. That just became my vocation over time. When World of Warcraft came out and the gold farmers in that first 2000 paper basically trashed the game. I became concerned enough that I thought this gold farming would disrupt the economies of these games to such an extent that they would fail. So that’s when I decided I was going to become the world’s first applied virtual economist and started developing new models and solutions to correct these economic flaws in our game designs such that we could make bigger games that were sustainable that wouldn’t be exploited by gold farmers.

The other game I’m working on right now that is also oxytocin oriented, I just started working with a very nice Canadian team with a bunch of veterans from the industry and that’s a game called Destiny’s Sword.

That game is also going to be interesting in that we’re actually modeling emotional stress and mental repercussions of combat in the gameplay.

Normally in a game, if you die, you just reset and you start over and there’s no harm, no foul and there’s no lasting effects from gameplay session to gameplay session.

But in this game, whatever you do on this day might have a lasting effect on your character the next day or even permanently and even change the personality of your units and your characters so I think that’s going to a be very successful model because it gives a much more realistic feel than what you’ve gotten in any previous game.

The team effects, the peer effects, everything is oriented towards increasing the attachment you feel for not only your units but also your teammates.

Max: Ramin, are there any questions that I’ve failed to ask that I’m just making up?

Ramin: Enumerable :)

Max: Well, I want to reassure our audience that I think both of us would enjoy doing this again and going perhaps further in depth into one of the topics we’ve covered because God knows we can get pretty deep into it. I would love to hear more.

Ramin: It’s just going to keep getting deeper and deeper because really if you’ve ever seen the Matrix series, what they described there is really not that far away. We’re rocketing towards the Matrix at a rate that it’s just hard to imagine unless you know the science and just what … How enthusiastically tech companies are raising what I’m starting to call physiologically driven design in the creation of their products.

Max: Well, hot damn. I’m looking forward to it. Let’s plan to have another conversation at some point about education in video games. I’ll poll our audience and find out which of the topics we’ve talked about today are most deserving of the next episode.

Ramin: That sounds great.

Max: Awesome.

Ramin: Thank you so much, Max.

Max: Thank you for doing this, Ramin.